Architecting the PhonePe Consumer app’s voice

How we defined a voice for that was consistently resonant across all contexts

November 24, 2025

What is a product’s voice and tone? A coat of paint on a product that works well? In some cases, maybe. But to us at PhonePe design, it works more as the foundational skeleton of a building on which everything else is built. The style of the facade matters, but true structural integrity comes from the non-negotiable guidelines that dictate how every component interacts to form a cohesive, resilient whole.

When working on the PhonePe 3.0 Redesign, we began at this foundational step: defining a voice that was consistently and authentically resonant across all touchpoints and contexts. Here’s what we learnt from that process.

Choose between attributes that have genuine tension

The way people generally frame brand attributes has often been counterproductive. Think warm vs. cold, engaging vs. boring. If you think about it, no brand has ever proudly declared "We choose to be cold and boring!" That’s like a restaurant saying "our food won't make you sick." It’s a given, so these become false choices.

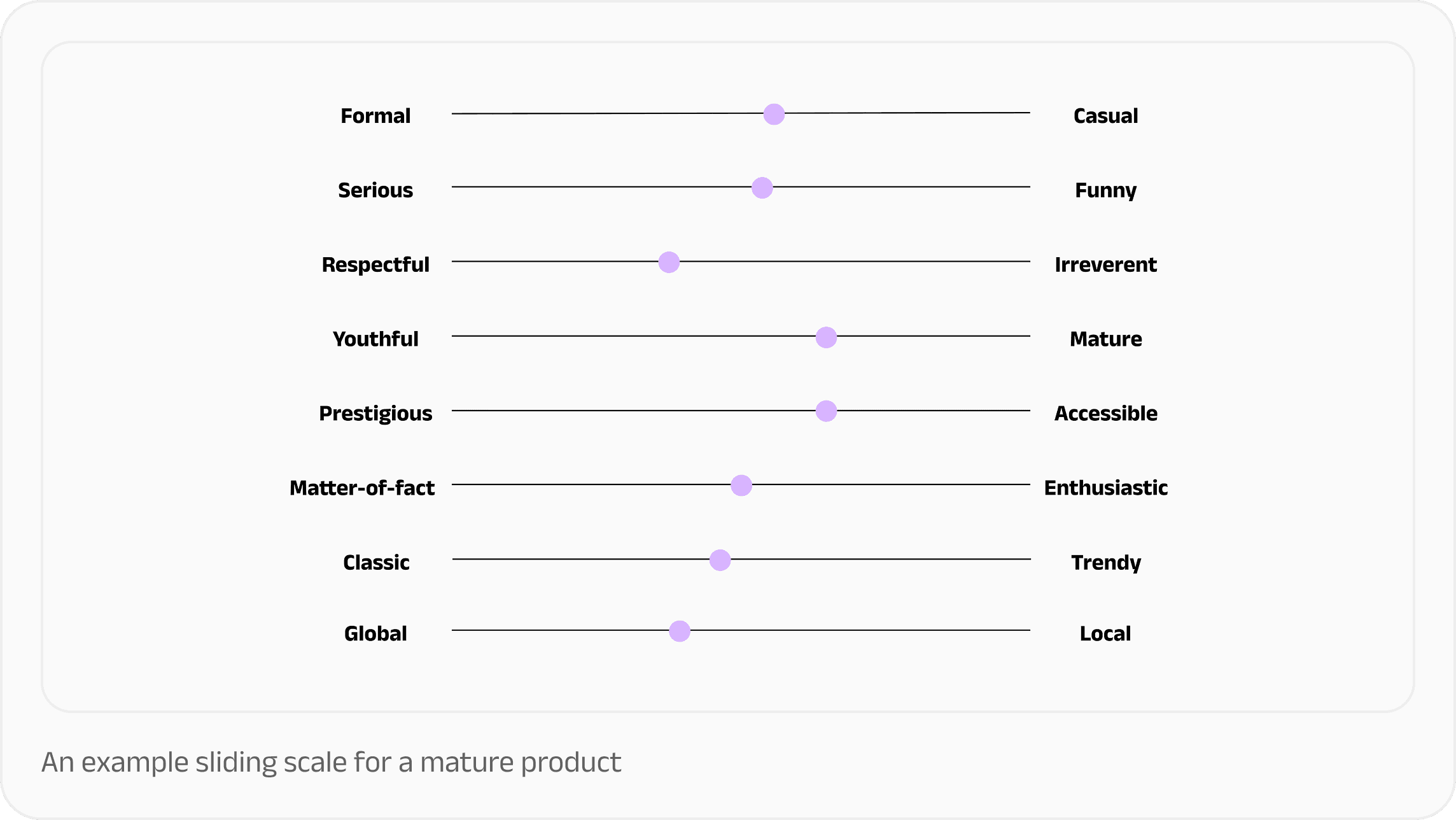

When we were working on the sliding scale of the PhonePe product’s voice, we kept in mind that meaningful brand positioning happens when you contrast two positive attributes that have genuine tension and tradeoffs. Each attribute is a valid choice with its own merits, target audience and treatment. Therefore, what we don’t choose would say as much as what we do choose.

We mapped voice qualities across several spectrums including: youthful vs mature, respectful vs irreverent, fun vs utilitarian, classic vs trendy, and so on.

Choosing between two good options with natural trade-offs helped define the character we wanted much more strongly.

For example, product messaging can be warm and gentle (kind), or it can be clear, direct, and transparent, even if the message is difficult (upfront).

Keep the defining team small

It can be tempting to involve entire teams in the brand voice definition exercise. However, there are merits to starting with a small group of key stakeholders. This tight, cross-functional group, guided by actual business and user data, can define a solid core voice without getting lost in a flood of early opinions.

In our case, we intentionally worked with org leaders who drive the narrative of the company in some shape or form. We consulted with the Heads of Public Relations, Investor Relations, Business, Product, Design, Brand, Internal Communications, Engineering, and Customer Support. We also took our early iterations all the way up to the PhonePe founders’ cabins. Their implicit knowledge and foresight about the company ensured we were defining a voice that was malleable to work with as the product evolved over time.

Once this foundation is stable, we recommend bringing in designers, marketers, copywriters and, soon after, other teams. These are people who will carry the voice throughout the product; their feedback is super useful in making sure the voice guidelines are intuitive and clear enough to implement.

Map tone to the emotion, not just the channel

A common trap for product teams is the "channel-first" framework. This dictates tone based solely on the platform. Think “our social media tone is playful, but our in-app copy is direct”.

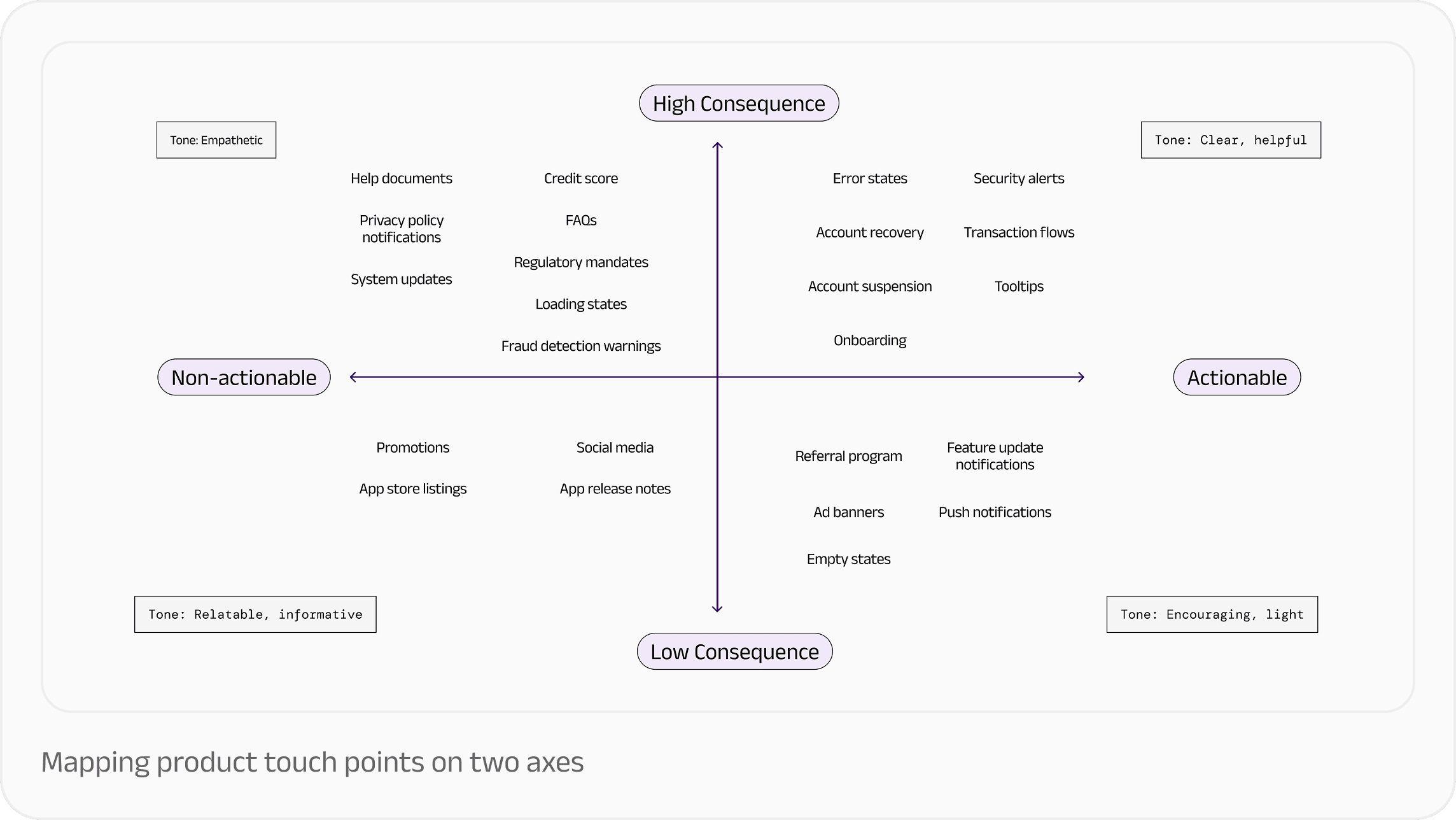

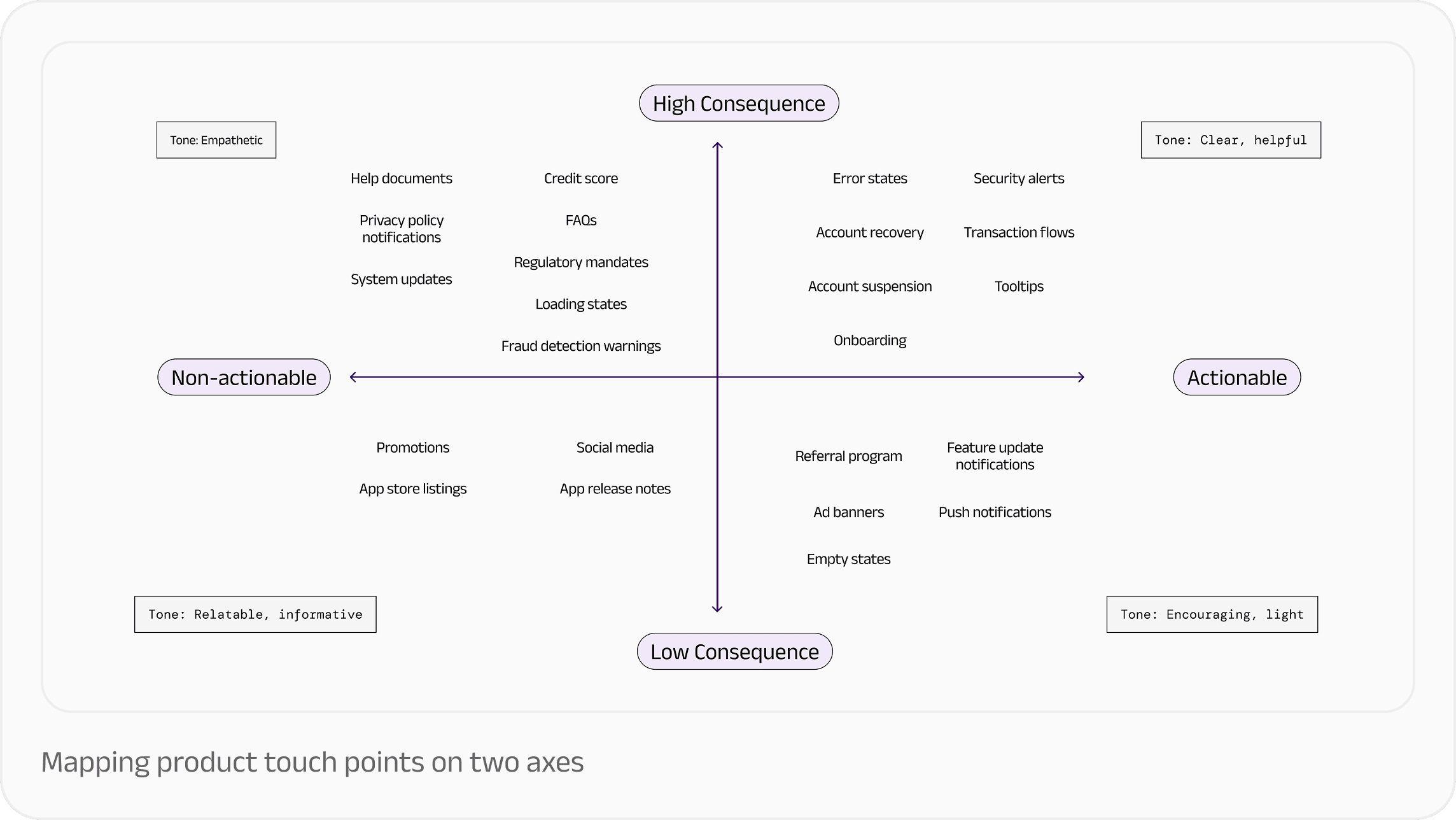

This approach fails because a user's emotional context can change dramatically within the same channel. A user's experience within that single channel isn't uniform. That's why we decided to map every interactive touchpoint against two key psychological axes:

consequence, which defines the importance or stress level of the message to the user, and

action, which defines whether the user needs to act on the message or is simply receiving it.

Consider the example of a "failed payment". This is a High-Consequence, Actionable scenario. The user is likely feeling anxious or frustrated. A direct tone might come off as rude or dismissive, which does nothing for their emotions. Alternatively, a direct plus reassuring tone does far more to assuage their anxiety and guide them to a solution.

This is the power of psychological mapping. It plays the critical, user-centric role of matching their emotional needs and lowering their cognitive load, especially in high-stress moments.

Cover the different manifestations of voice

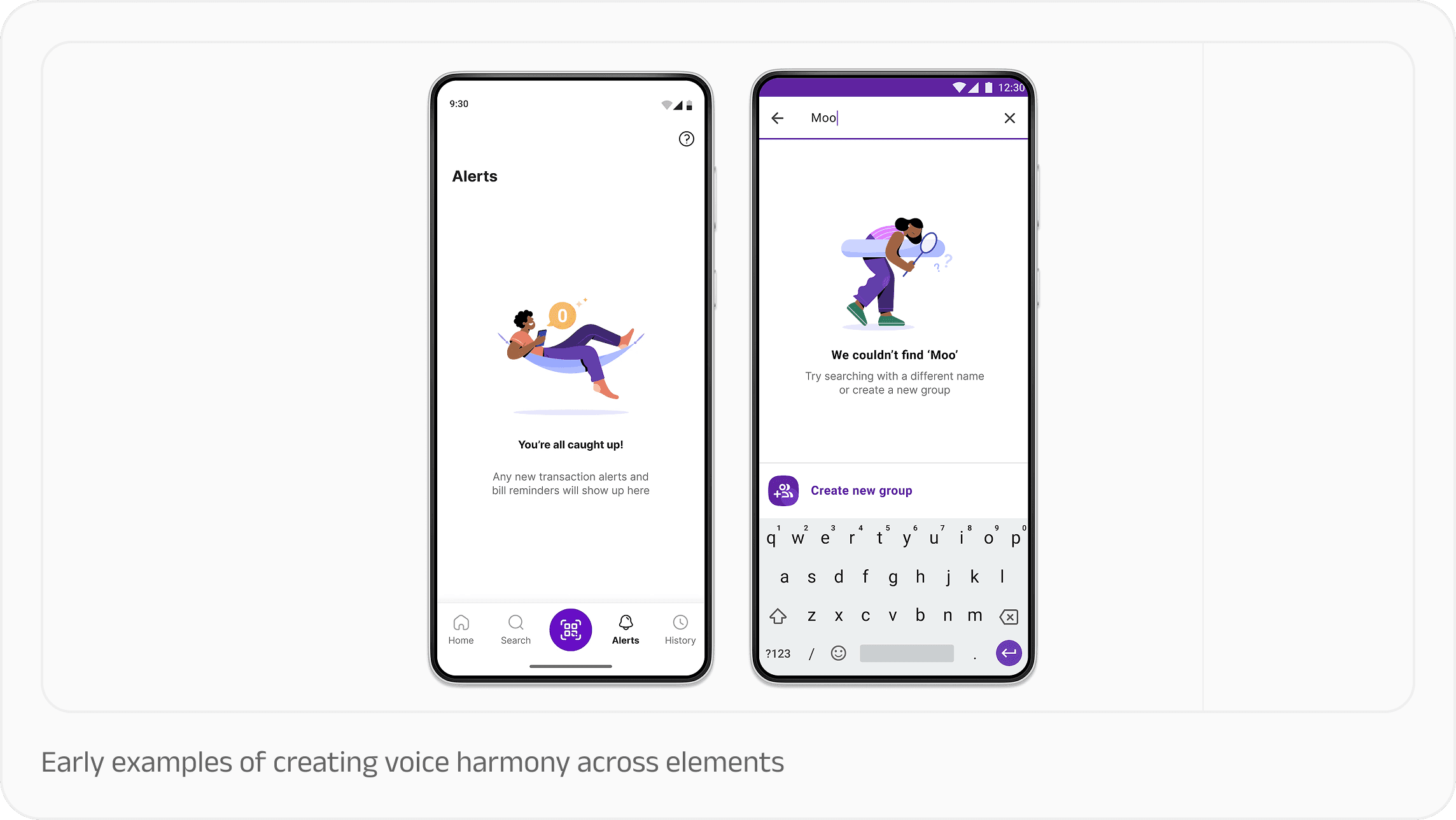

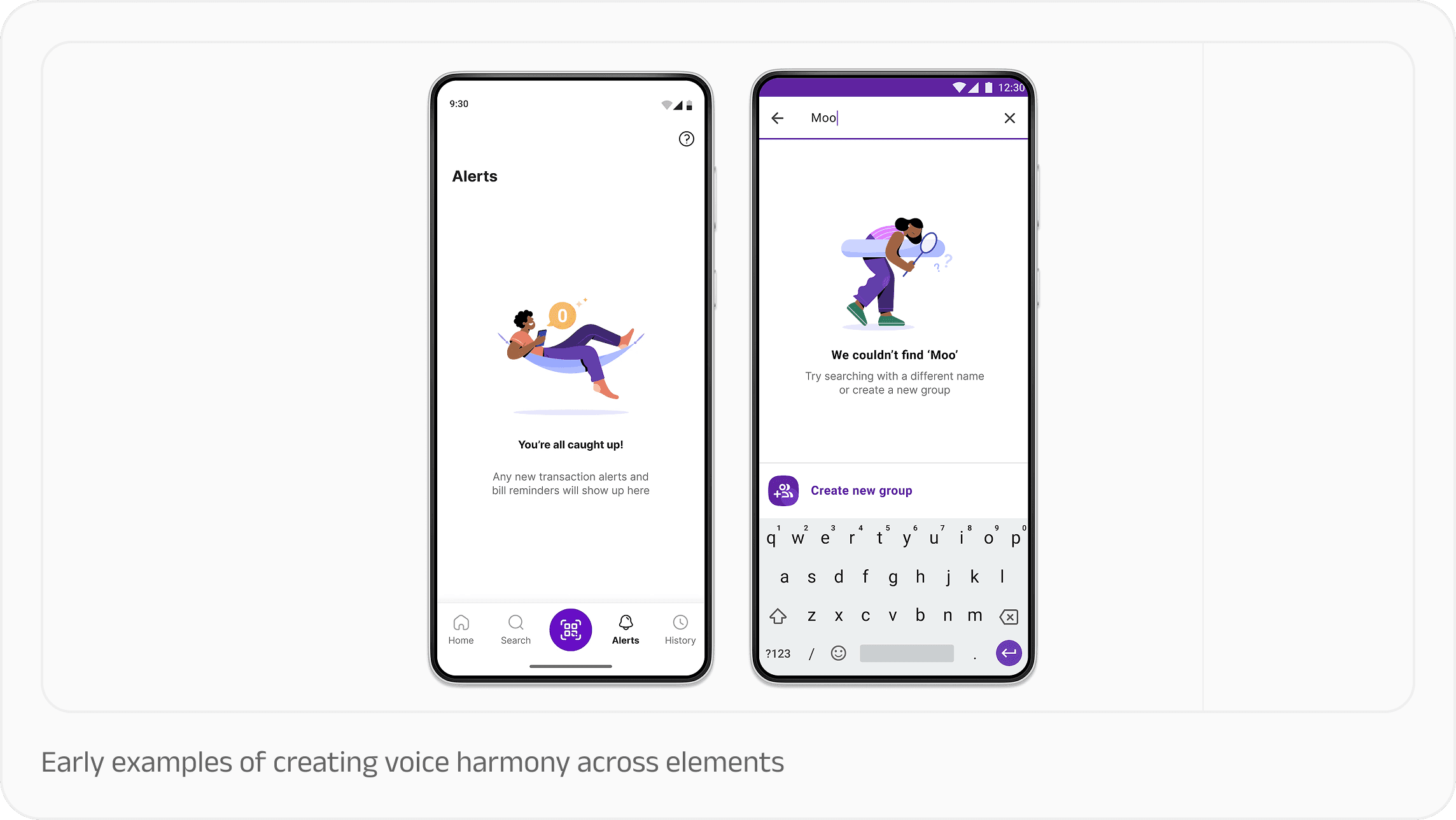

When thinking about voice, the default manifestation is often the words you see on the screen. But think back to digital products that seem like everything works together, from illustrations and type to colours and iconography. Why do they seem that cohesive? It’s most likely because they’re all channeling the voice of the product.

When designing PhonePe 3.0, we ran an experiment where we chose screens and created two variations of each: one where only the copy hit the right voice and tone, and one where the illustrations, colours, and even the angle of button corners channeled that same brand voice. The difference was night and day.

When we paired an empathetic line of copy with a loud and anxious illustration, the overall effect of the screen was negative. Joyful and delightful text felt dampened when placed against a generic illustration style. But when all the elements on the screen conveyed the same emotion and message, the screen addressed the psychological state of the user a lot better.

Aim to create the path of least resistance

In product development, writing copy happens at different stages of the cycle, and almost always under tight deadlines. On top of that, the people writing copy might not always be writers, especially in leaner teams. A PM might step in, or an engineer, or even a marketer. If the voice and tone guide requires them to read a 50-page document or spend 10 minutes debating the nuance of a voice principle, they will skip it. What they need is a simple, definitive answer right now.

The best, most applicable guidelines are almost paint-by-numbers. They need to offer simple, non-negotiable rules that reduce cognitive load and eliminate decision fatigue.

For example, instead of saying "Titles should be concise and reflective of the context," which is open to interpretation, a simple rule like "Titles are always 5 words or less" gives the writer an objective measurement they can apply in seconds. These direct constraints are also easy to check and enforce, making adherence the path of least resistance.

Build the floor before the ceiling

In our experience, your first goal with any voice and tone guide should be to prevent bad writing. Once that’s solid, you can focus on making good writing possible.

What does that mean?

The initial set of rules must be focused on preventing the worst possible outcome like confusing error messages, wordy buttons, grammatical errors, or tone that undermines trust. It ensures that even the fastest, most distracted copy still maintains clarity and basic human decency.

Once the fundamental structure is stable, you can introduce more nuanced guidance. This could be advice on advanced empathy in difficult scenarios, or ways to introduce delight in masthead copy. This is where you equip the experienced writers of the team to create truly great copy, as any mistakes have already been filtered for by the basic, non-negotiable rules.

Test on your worst-case scenarios

We highly recommend testing your voice guidelines on the hardest copy: legal disclaimers, system error messages, deletion confirmations, and the like. If your voice can survive there while remaining clear and human, it can handle everything else much more easily.

For example, if your brand’s voice is irreverent, how will it apply in a situation where a user needs to be notified about a data loss event? In that case, an irreverent voice might end up seeming disrespectful or insufferable. But reverting to total legal speak might make the user feel even more alienated from your brand at the most crucial time.

This sort of stress test is absolutely necessary to ensure your voice can apply across the board, and how it applies can be baked into the guidelines.

Nominate guideline champions

Creating and documenting the voice and tone guide is one half of the battle. The other half is ensuring it’s adhered to.

In many companies, UX writing teams are leaner, or the responsibility of writing copy stretches across different teams including design, product management, marketing, and engineering. People will have different levels of comfort and familiarity with the guidelines, or might be used to a certain way of working and writing.

To ensure the guide is applied consistently and thoroughly throughout the product, we appointed guideline champions in each team. These people became advocates who ensured the guide was followed and referred to in meetings and sprints. They would also highlight inconsistencies in the product where they catch it, and act as a bridge between the guide’s custodians and its users.

There’s also a second-order benefit: doing this ensures that adhering to the playbook remains a collective responsibility, rather than the purview of one team.

In conclusion

What we learned from our voice and tone work over the past year is that a product’s voice is ultimately a system of applied empathy. It’s not a set of lines, but an operational framework for how the product behaves, especially under pressure. This is how a brand’s character moves from an abstract idea into a tangible, reliable, and holistic experience for crores of people.

What is a product’s voice and tone? A coat of paint on a product that works well? In some cases, maybe. But to us at PhonePe design, it works more as the foundational skeleton of a building on which everything else is built. The style of the facade matters, but true structural integrity comes from the non-negotiable guidelines that dictate how every component interacts to form a cohesive, resilient whole.

When working on the PhonePe 3.0 Redesign, we began at this foundational step: defining a voice that was consistently and authentically resonant across all touchpoints and contexts. Here’s what we learnt from that process.

Choose between attributes that have genuine tension

The way people generally frame brand attributes has often been counterproductive. Think warm vs. cold, engaging vs. boring. If you think about it, no brand has ever proudly declared "We choose to be cold and boring!" That’s like a restaurant saying "our food won't make you sick." It’s a given, so these become false choices.

When we were working on the sliding scale of the PhonePe product’s voice, we kept in mind that meaningful brand positioning happens when you contrast two positive attributes that have genuine tension and tradeoffs. Each attribute is a valid choice with its own merits, target audience and treatment. Therefore, what we don’t choose would say as much as what we do choose.

We mapped voice qualities across several spectrums including: youthful vs mature, respectful vs irreverent, fun vs utilitarian, classic vs trendy, and so on.

Choosing between two good options with natural trade-offs helped define the character we wanted much more strongly.

For example, product messaging can be warm and gentle (kind), or it can be clear, direct, and transparent, even if the message is difficult (upfront).

Keep the defining team small

It can be tempting to involve entire teams in the brand voice definition exercise. However, there are merits to starting with a small group of key stakeholders. This tight, cross-functional group, guided by actual business and user data, can define a solid core voice without getting lost in a flood of early opinions.

In our case, we intentionally worked with org leaders who drive the narrative of the company in some shape or form. We consulted with the Heads of Public Relations, Investor Relations, Business, Product, Design, Brand, Internal Communications, Engineering, and Customer Support. We also took our early iterations all the way up to the PhonePe founders’ cabins. Their implicit knowledge and foresight about the company ensured we were defining a voice that was malleable to work with as the product evolved over time.

Once this foundation is stable, we recommend bringing in designers, marketers, copywriters and, soon after, other teams. These are people who will carry the voice throughout the product; their feedback is super useful in making sure the voice guidelines are intuitive and clear enough to implement.

Map tone to the emotion, not just the channel

A common trap for product teams is the "channel-first" framework. This dictates tone based solely on the platform. Think “our social media tone is playful, but our in-app copy is direct”.

This approach fails because a user's emotional context can change dramatically within the same channel. A user's experience within that single channel isn't uniform. That's why we decided to map every interactive touchpoint against two key psychological axes:

consequence, which defines the importance or stress level of the message to the user, and

action, which defines whether the user needs to act on the message or is simply receiving it.

Consider the example of a "failed payment". This is a High-Consequence, Actionable scenario. The user is likely feeling anxious or frustrated. A direct tone might come off as rude or dismissive, which does nothing for their emotions. Alternatively, a direct plus reassuring tone does far more to assuage their anxiety and guide them to a solution.

This is the power of psychological mapping. It plays the critical, user-centric role of matching their emotional needs and lowering their cognitive load, especially in high-stress moments.

Cover the different manifestations of voice

When thinking about voice, the default manifestation is often the words you see on the screen. But think back to digital products that seem like everything works together, from illustrations and type to colours and iconography. Why do they seem that cohesive? It’s most likely because they’re all channeling the voice of the product.

When designing PhonePe 3.0, we ran an experiment where we chose screens and created two variations of each: one where only the copy hit the right voice and tone, and one where the illustrations, colours, and even the angle of button corners channeled that same brand voice. The difference was night and day.

When we paired an empathetic line of copy with a loud and anxious illustration, the overall effect of the screen was negative. Joyful and delightful text felt dampened when placed against a generic illustration style. But when all the elements on the screen conveyed the same emotion and message, the screen addressed the psychological state of the user a lot better.

Aim to create the path of least resistance

In product development, writing copy happens at different stages of the cycle, and almost always under tight deadlines. On top of that, the people writing copy might not always be writers, especially in leaner teams. A PM might step in, or an engineer, or even a marketer. If the voice and tone guide requires them to read a 50-page document or spend 10 minutes debating the nuance of a voice principle, they will skip it. What they need is a simple, definitive answer right now.

The best, most applicable guidelines are almost paint-by-numbers. They need to offer simple, non-negotiable rules that reduce cognitive load and eliminate decision fatigue.

For example, instead of saying "Titles should be concise and reflective of the context," which is open to interpretation, a simple rule like "Titles are always 5 words or less" gives the writer an objective measurement they can apply in seconds. These direct constraints are also easy to check and enforce, making adherence the path of least resistance.

Build the floor before the ceiling

In our experience, your first goal with any voice and tone guide should be to prevent bad writing. Once that’s solid, you can focus on making good writing possible.

What does that mean?

The initial set of rules must be focused on preventing the worst possible outcome like confusing error messages, wordy buttons, grammatical errors, or tone that undermines trust. It ensures that even the fastest, most distracted copy still maintains clarity and basic human decency.

Once the fundamental structure is stable, you can introduce more nuanced guidance. This could be advice on advanced empathy in difficult scenarios, or ways to introduce delight in masthead copy. This is where you equip the experienced writers of the team to create truly great copy, as any mistakes have already been filtered for by the basic, non-negotiable rules.

Test on your worst-case scenarios

We highly recommend testing your voice guidelines on the hardest copy: legal disclaimers, system error messages, deletion confirmations, and the like. If your voice can survive there while remaining clear and human, it can handle everything else much more easily.

For example, if your brand’s voice is irreverent, how will it apply in a situation where a user needs to be notified about a data loss event? In that case, an irreverent voice might end up seeming disrespectful or insufferable. But reverting to total legal speak might make the user feel even more alienated from your brand at the most crucial time.

This sort of stress test is absolutely necessary to ensure your voice can apply across the board, and how it applies can be baked into the guidelines.

Nominate guideline champions

Creating and documenting the voice and tone guide is one half of the battle. The other half is ensuring it’s adhered to.

In many companies, UX writing teams are leaner, or the responsibility of writing copy stretches across different teams including design, product management, marketing, and engineering. People will have different levels of comfort and familiarity with the guidelines, or might be used to a certain way of working and writing.

To ensure the guide is applied consistently and thoroughly throughout the product, we appointed guideline champions in each team. These people became advocates who ensured the guide was followed and referred to in meetings and sprints. They would also highlight inconsistencies in the product where they catch it, and act as a bridge between the guide’s custodians and its users.

There’s also a second-order benefit: doing this ensures that adhering to the playbook remains a collective responsibility, rather than the purview of one team.

In conclusion

What we learned from our voice and tone work over the past year is that a product’s voice is ultimately a system of applied empathy. It’s not a set of lines, but an operational framework for how the product behaves, especially under pressure. This is how a brand’s character moves from an abstract idea into a tangible, reliable, and holistic experience for crores of people.

Read next

If this excites you,

let's build together

Sign up to get updates about new essays and design events

If this excites you,

let's build together

Sign up to get updates about new essays and design events

If this excites you,

let's build together

Sign up to get updates about new essays and design events